What we know

The week of November 17, 2025, sick and dying salamanders were reported from a private collection of the genus Salamandra. Members of the North American Bsal Task Force were notified, and samples from affected salamanders were submitted to the University of the Tennessee and U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center for diagnostic testing. Scientists are actively working to identify the pathogen.

The collaborative diagnostic response team was quickly able to rule out Bsal (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans), an invasive fungal pathogen that can cause lethal disease in salamanders which has not yet been detected in the United States. The other commonly known amphibian pathogens Bd (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) and Ranavirus were also ruled out. Scientists are testing for additional pathogens and suspect the unknown pathogen, which could be a fungus, virus or bacterium, may be from another continent.

Sick and exposed salamanders have been quarantined, and current information indicates this outbreak is limited in scope. Common signs of this disease include abnormal skin shedding/sloughing, skin lesions or ulcerations, and changes in behavior such as sluggishness or reduced appetite.

To date, this disease has only been seen in species in the genus Salamandra. Susceptibility and risk of disease within other native and non-native salamander species is unknown. Researchers are working to understand potential risk to native species.

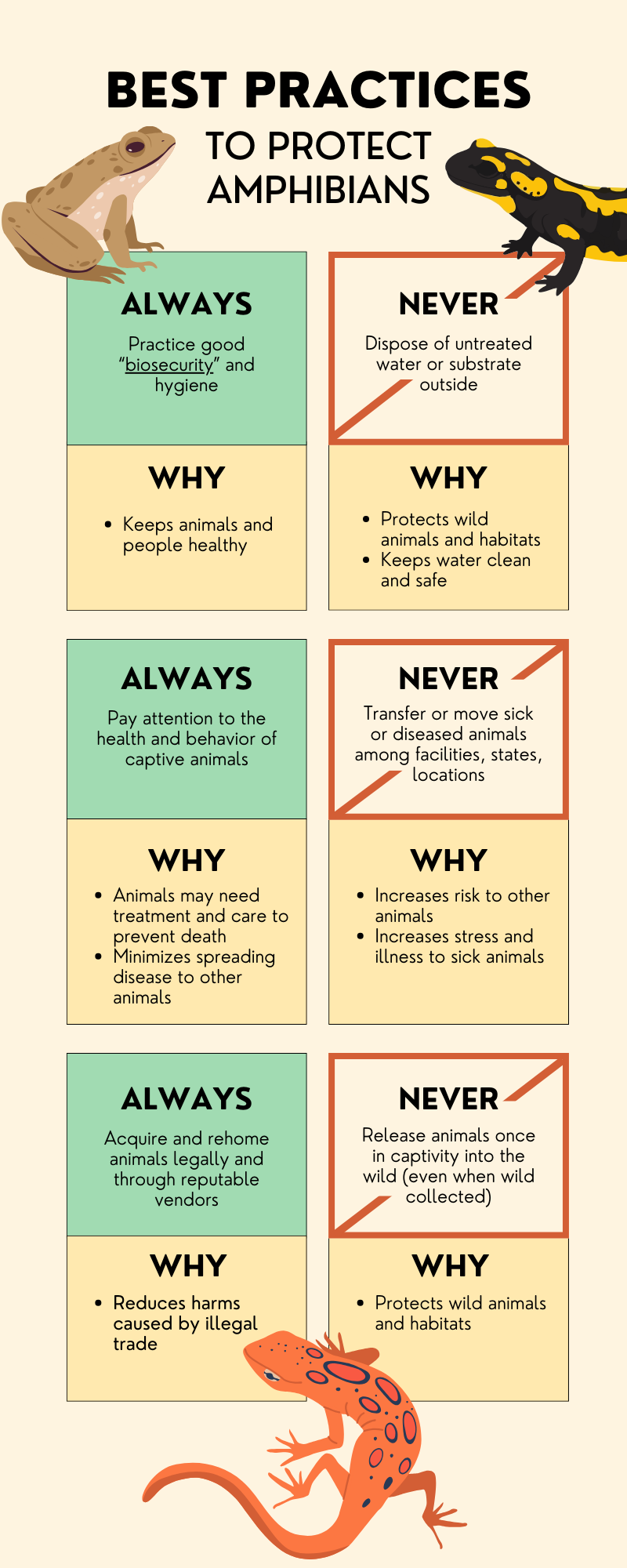

The disease can be transmitted among salamanders if they are co-housed or if good biosecurity (hygiene) practices are not followed. Scientists suspect that exposed, asymptomatic animals could still be infected and transmit disease and are working with private collectors to closely monitor the health of affected animals and achieve and sustain containment. The non-profit organization Healthy Trade Institute is leading forward tracing efforts and interacting with businesses and pet owners that may be impacted. Members of the North American Bsal Task Force, amphibian disease experts and HTI are working together to support containment, identify the cause of disease and control the pathogen.

We have no evidence that this disease presents a human-health risk or risk to non-amphibian pets. However, maintaining good personal safety practices is important because we do not know the pathogen involved.

What should you do?

While the outbreak is believed to be controlled, it is possible that this unknown pathogen is in the US pet trade elsewhere. The early detection and rapid response of multiple partners, businesses and pet owners serves as a reminder that vigilant and cooperative monitoring of captive and wild amphibian and reptile health is the most effective way to reduce the risk of invasive pathogens and protect our diverse native amphibians, reptiles and habitats.

If you’re a pet amphibian owner or business that sells pet amphibians, we recommend that you:

- Say something when you see something: Watch for clinical signs of disease such as skin sloughing, dark, dry skin patches, skin lesions, bleeding or changes in behavior.

- Anyone who sees signs of illness in captive salamanders should report their finding to the Healthy Trade Institute or reach out directly to the contacts below. It is critical that animal care takers and enthusiasts do not move, transport, dispose of or release potentially sick animals without professional guidance.

- Always maintain good personal safety practices, even when animals appear healthy. This includes: using best biosecurity practices during animal care, washing hands after handling animals and cleaning housing, and using separate spaces for your own food preparation and materials for your animals.

- Always acquire and rehome animals legally and through reputable vendors.

Who should you contact?

If you’re a pet amphibian owner or business that sells pet amphibians and are concerned about the health of your animals, you may contact Matt Gray, President and CEO of the HTI at: mgray@healthytrade.org, 865-385-0772; or call 617-505-8165.

If you witness symptoms of illness or large mortality event in wild salamanders, or any population of amphibians or reptiles, we recommend that you:

- Report your observations to the Herp Disease Alert System or USGS National Wildlife Health Center via web, nwhc-epi@usgs.gov or 608-270-2480. These wildlife disease experts work with the appropriate natural resources agencies to investigate concerns. Receiving these types of reports is essential to evaluate the threat of diseases such as Bsal and protect wild North American species.

About our Partners

The HTI is a 501c3 non-profit organization that is dedicated to helping businesses and pet owners reduce pathogens in trade that negatively affect amphibians and reptiles. The HTI is endorsed by the Pet Advocacy Network and a supporter of the U.S. Association of Reptile Keepers. Our staff and partners include representatives in the pet industry and experts in amphibian and reptile diseases and care. We also serve as a liaison between the pet trade, scientists, and veterinarians to ensure effective and efficient disease response. For disease testing and response, personal information remains confidential.

The U.S. Geological Survey provides science for managing amphibian diseases through the National Wildlife Health Center and the Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative. USGS monitors amphibian pathogens and conducts disease research throughout the country, and the National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisconsin coordinates the health screenings and investigations of amphibian mortalities (e.g., identification, pathology) in addition to collaborating on many disease research projects, including preparing for emerging diseases, such as our work on Bsal.